TEI ecosystems for digital editions: Why can’t they be interoperable and interchangeable?

In her keynote address at the 2016 conference meeting of the Text Encoding Initiative

in Vienna, Tara Andrews broached the issue of whether TEI can really be considered

a

de facto standard

for the encoding and interchange of digital texts.[1] Her talk broached a long-recognized issue that the TEI Guidelines permit too

many choices, such that there is very little that can be practically interoperable

via

simple programmatic mapping from one TEI project’s markup ecosystem to another. The

TEI

might well be a garden of too many forking paths, too richly labyrinthine because

too

entertaining of multiple modes of expression. Although Andrews’s talk specifically

addressed the lack of interoperability in scholarly editions built with TEI and a

lack

of available software tools to process universally all TEI documents, we might take

this

as a more fundamental concern that the TEI has not fulfilled a more basic promise

of its

origins. That is, beyond its difficulties in achieving interoperability, perhaps the

Text Encoding Initiative as a wild ecosystem fails to live up to the ideal vaunted

in

the title of its documentation as Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and

Interchange

. Perhaps, too, it might be said that those of us who work with

TEI do not sufficiently prioritize either interoperability or interchangeability in

our

projects. The goal of universal interoperation may simply be unrealistic for rich

variety of applications employed around the world for the TEI, but interoperability

among related kinds of documents would seem practically attainable. In the case study

of

the Frankenstein Variorum project presented in this paper, we exemplify and attempt

to

solve the problem of achieving interchangeability among different digital editions

of

the same novel in variant forms, by developing intermediary stand-off markup designed

to

bridge

different TEI markup ecosystems with each their own priorities

for description and representation of the novel.

Of course, to be interoperable is not the same thing

as to be interchangeable. Syd Bauman’s definitive

Balisage paper of 2011, Interchange vs. Interoperability

, is especially helpful in

discussing and evaluating the different priorities represented by each term.

Interoperability (or interoperationality) depends on whether a document can be processed

by a computer program without human intervention. Interchangeability, on the other

hand,

involves human interpretation and is supported by community-defined vocabularies and

well-written documentation. While TEI users often wish to prioritize ready

interoperability, as in preparing Lite

or Simple

code

easily interpretable by a software tool (say, a TEI plugin for a document viewer),

Bauman finds that this is exceedingly difficult to achieve without sacrificing

expressive semantics to the requirements of a software package. By contrast,

interchangeable encoding, especially encoding that permits what Bauman calls

blind interchange

, prioritizes human legibility such that

interpreting files does not require contacting the original encoder for help in

understanding how the data was marked. Interchangeable data achieves semantic richness

and lasting value without needing to predict the operating systems and software

available to deliver it. It also does not require the forced simplification that

interoperability demands for suiting what tools are or might become available.

Bauman represents these goals as at odds with one another, stressing the point that

interoperability is a matter of machine interpretation without human intervention:

interoperability and expressiveness are competing goals constantly in tension

with each other. While the analogy is far from exact, interoperationality is akin

to

equality, and expressiveness is akin to liberty.

The equality Bauman

ascribes to interoperable would seem to raze the complexity of a project, levelling

all

projects to simple terms common to a convenient universal application. Perhaps, though,

enhancing the interchangeability of documents could create better conditions for

interoperation that do not sacrifice the complex ontologies and research questions

of

data-driven TEI markup. Much depends on how we conceive of machine interoperation,

our

awareness of the suitability (and limits) of the tools we apply, and the constructions

we develop to cross-pollinate

projects developed in distinct

ecosystems.

Traditionally, the TEI has cared about both ideals. As Elli Mylonas and Allen Renear

discussed in 1999, TEI’s development of a language for data description and interchange

helped to build and support an international research community with a tool for

scholarship while also intervening in the proliferation of systems for

representing textual material on computers. These systems were almost always

incompatible, often poorly designed, and growing in number at nearly the same rapid

rate as the electronic text projects themselves.

[2]. While promoting blind interchange, TEI projects support development of

specialized tools for constructing digital editions in particular, and of course this

is

where we run amok with the interoperability challenge. Optimally developers who work

with TEI approach software tools with the caveat that some customization might be

necessary to adapt the tool to respond to the distinctiveness of the data rather than

the other way around, and that puts us into experimental territory as

tinkerers

or refiners of tools.

In the history of preparing digital texts with markup languages, whether in early HTML, SGML, or XML, markup standards tensed between two poles:

-

the acknowledgement of a coexistence of multiple hierarchical structures, and

-

the need to prioritize a single document hierarchy in the interests of machine-readability, while permitting signposts of overlapping or conflicting hierarchies as of secondary importance.[3]

read aroundconficting hierarchies, we require a third alternative that does not place coexistence in an oppositional camp, but rather prioritizes lateral intersections without sacrificing data curated in distinctly different structures. Makers of genetic and variorum editions (as for example the genetic Faust edition) find ourselves in this intermediary third position, when multiple encoding structures must co-exist and correlate to achieve a meaningful comparison of editions.[4] To produce an intermediating structure, the original hierarchies need to be reconceived in dynamic terms. We need to question and observe, where are their flex points for conversion from containment structures to loci of intersection? That, of course, is a determination reliant on interchange, in support of interoperationality.

To be clear, the work we have done is in support of interoperationality across encoding

ecosystems of the TEI. With this paper, we are not proclaiming a universal solution

to make the TEI itself be inherently interoperable.

We cannot simply take the original TEI or early HTML of the source editions we need

to compare in our variorum project, and drop the files unmediated into a collating

system to compare with one another. Indeed, as Desmond Schmidt defines interoperability,

it is the

property of data that allows it to be loaded unmodified and fully used in a variety of software applications

, and as exemplars of the interoperability ideal he indicates the marvellous capacity

of many web browsers able to read and parse and interact with HTML and SVG.

Here the lack of ambiguity or expressiveness (or illocutionary force

and human subjectivity that Schmidt ascribes as the significant obstacle to interoperability

in the TEI), simply makes it possible for software to interpret encoding in a consistent

and reliable way.[5]. As we see it, however, interoperability is not an all-or-nothing proposition, because

software tools are neither simply compatible nor incompatible with our documents.[6] We contend that there is no perfect interoperability, even in the software tools

that we expect to be universally compatible. We do not mean that designing for interoperability

is never worth the trouble, but rather that all-or-nothing arguments about it are

not especially helpful to the interests of textual scholarship. We assert with Martin

Holmes that if designers of TEI editions want to make it easy for others to re-purpose

TEI encoding, we generate alternative encodings of project-specific XML for the specific

purpose of enhancing interchange. In so doing we make it possible to build the tools

of interoperability that do not sacrifice the cross-walkable semantics that drive

scholarship and make it possible for us to share, repurpose, and build on each others’

work. We will need to interpret our own data structures to define relationships with

other ecosystems, and express these relationships in what shared vocabularies we use

to communicate with one another. As Holmes observes, By putting some effort into providing a range of different versions of our XML source

encodings, targeted at different use-cases and user groups, we can greatly facilitate

the re-use of our data in other projects; this process causes beneficial reflection

on our own encoding practices, as well as an additional layer of documentation for

our projects.

[7]

The most helpful part of Desmond Schmidt’s article of 2014 is his call to make digital

editions more interoperable by working with stand-off mechanisms for annotation, with

attention to intersection points in conflicting hierarchies. However, we do not see

that Schmidt’s solution of splitting the text into layers

on its own is going to enhance the kind of interoperation we need, and our needs

and interests are not uncommon in textual scholarship. We wish to be able to integrate

the elaborately descriptive markup of a diplomatic edition (with additions and deletions

and shifts of hands) much like the example Schmidt himself provides in section 5 of his article, into a comparison with other digital editions of print versions of this work, in

a way that preserves the information about handshifts encoded into the diplomatic

edition (with additions and deletions and shifts of hands) and makes it available

for comparison with other digital editions of print versions of this work. Indeed,

we see ourselves as curating the original markup from our source documents to preserve

its information within the Variorum edition we are developing. In the experience we

describe in this paper, we treat the markup itself as patterned text, programmatically

accessible for selective masking from the automated processes we want to run for machine

collation and afterward for constructing the variorum. Dividing the complex markup

of insertion and deletion events into separate layers pointing at the document might

be a solution for the kind of operation Schmidt needs his limited tools to perform,

but for our purposes, the source editions we are working with are long-established

and not intractable to computational extraction and sequencing. Altering that markup

is not really an option for us and it is so cleanly encoded and well documented that

we would rather apply our computational tools to read and parse it, and to build from

it rather than to reconstruct it.

From the experience of investigating diverse systems of markup applied to multiple

versions of one novel from the 1990s to the 2010s, we do not find generalized dismissals

of TEI markup as subjective

to be compelling enough to dismiss the many information-rich projects built with

the TEI over decades. Indeed, we need to work with those editions and the rich data

they contain, to advance scholarship rather than reinventing it as if its encoding

were value-less to outsiders. To advance the interests of scholarship involves respecting the encoding of earlier times and places, not only acknowledging its complexity and

shortfalls, but building with it something that will be richly informative and available

that was not before. Certainly it is difficult to find a place for a diplomatic edition

in a variorum context, but when we build bridges for interchange, we create conditions

for interoperation. In the case of our Variorum project, we need to do the work of

interchange to make automated collation possible. Even if that collation is not perfect,

and requires human intervention, can we ever expect interoperation simply to work perfectly

without some human intervention? The efforts in building digital editions are necessarily

complex, and we rely on interoperation to help build the very bridges we need for

our Variorum edition to connect digital editions that remain in their own distinct

ecosystems.

Building a variorum edition from multiple sources

A typical process of collation involves the comparison of textual units (typically words) across multiple sources of the same text (e.g. between a manuscript, a copy, a first print, etc.). This is often the first fundamental operation that textual scholars perform in preparation of a critical edition. In our specific case, the collation needs to process previously encoded editions of the sources we want to compare. In order to compare these editions, their hierarchies must be dismantled and flattened in order for the collation to be able to account for changes in structure, such as a paragraph break in one edition that is missing in the others, or a handwritten deletion in a manuscript that shows up in a print edition. The collation needs to be able to cut across the original document hierarchies and yet preserve the information from the original markup.

To align such variations is necessarily going to disrupt the hierarchical encoding

of each source edition, but another way to think of the collation process is as a

building tool, a kind of weaving or bridge-building process, creating a new kind of

hierarchy that intersects the source editions. The new hierarchy contains arches and

connecting spans across formerly isolated monoliths. Our use of the terms

arch

, bridge

, or span

is more than a

metaphor here, but drawn from a graph-based model of text on which, not coincidentally,

CollateX was designed for locating variants in documents. [8]

We describe one such effort in the Frankenstein Variorum Project.[9]. Much of our work has involved preparing documents for processing with CollateX software, which automates the

location of alignments and deltas in multiple versions of a text. We have had to contend

a challenge of interchange to be able to make meaningful comparisons of digital editions

made at different times by different editors, with a goal to prepare a digital variorum

edition of five versions of Frankenstein in TEI. We first up-converted two of our

collation source documents from the 1990s web 1.0 HTML encoding of the Pennsylvania

Electronic Edition of Frankenstein for the 1818 and

1831 editions.[10] We needed to find a way to collate these editions with the Shelley-Godwin

Archive’s diplomatic edition of the manuscript notebooks of 1816, the only known

existing drafts of the novel held at the Bodleian Library.[11] We are also newly incorporating a little-known edition of the novel’s 1823

publication produced from corrected OCR of a Google Books facsimile, together with

transcription of Mary Shelley’s handwritten revision notes on a copy of the 1818

publication known as the Thomas copy

held at the Morgan Library and Museum.[12] Our collation should yield a meta-narrative of how Frankenstein changed over time in five versions that passed through

multiple editorial hands. It is widely understood that the 1831 edition diverges sharply

from the first print edition of 1818, adding new material and changing the relationships

of characters. Less known is how the notebook material compares with the print editions,

and how much we can identify of the persistence of various hands involved in composing,

amending, and substantially revising the novel over the three editions. For example,

to

build on Charlie Robinson’s identification of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s hand in the

notebooks, our collation can reveal how much of Percy’s insertions and deletions survive

in the later print editions. Our work should permit us to survey when and how the

major

changes of the 1831 text (for example, to Victor Frankenstein’s family members and

the

compression and reduction of a chapter in part I) occurred. We preserve information

about hands, insertions, and deletions in the output collation, to serve as the basis

for better quantifying, characterizing, and surveying the contexts of collaboration

and

revision in textual scholarship.

The three print editions and extant material from three manuscripts are compared in

parallel, to indicate the presence of variants in the other texts and to be able to

highlight them based on intensity of variance, to be displayed like the highlighted

passages in each visible edition of The Origin of

Species in Darwin Online.[13] Rather than any edition serving as the lemma or grounds for collation

comparison, we hold the collation information in stand-off markup, in its own XML

hierarchy. That XML bridge

expresses relationships among the distinct

encodings of diplomatic manuscript markup in which the highest level of hierarchy

is a

unit leaf of the notebook, with the structural encoding of print editions organized

in

chapters, letters, and volumes. While the apparently nested structure of these divisions

might seem the most meaningful way to model Frankenstein, these pose a challenge to textual scholarship in their own

right. As Wendell Piez has discussed, Frankenstein’s

overlapping hierarchies of framing letters and chapters have led to inconsistencies

in

the novel’s print production. Piez deploys a non-hierarchical encoding of the novel

on

which he constructs an SVG modeling (in ordered XML syntax) of the overlap itself.[14] Our work with collation depends on a similar interdependency of structurally

inconsistent encoding.

Overview of the bridge-building process

Our method involves three stages of structural transformation, each of which disrupts the hierarchies of its source documents:

-

Preparing texts for collation with CollateX,

-

Collating a new "braided" structure in CollateX XML output, which positions each variant in its own reading witness,

-

Transforming the collation output to survey the extents and kinds of variation, and to build a digital variorum edition.

In the first stage, we adapt the source code from the Shelley-Godwin Archive

(specialized TEI for the encoding of manuscript page surfaces) and from the

Pennsylvania Electronic Edition (PAEE) (HTML 1.0 from the mid 1990s marking

paragraphs and sectional headings) to create new forms of XML to carry predictable

markers to assist in alignment. These new, pre-collation editions are resequenced,

for example, we move marginal annotations from the end of the XML document into

their marked places as they would be read in the manuscript notebook. The texts from

the PAEE are corrected against photofacsimiles of first publications of the novel

in

1818 and 1831. They are also differently chunked

than their source

texts, resizing the unit file so that each represents an equivalent portion small

enough to collate meaningfully and large enough that each document demonstrably

aligns with the others at its start and end points. We prepared 33 collation units

of the novel. XML matching the pre-collation format is prepared from OCR texts of

the 1823 edition. Building from the 1818 collation units, we add in encoded transcriptions

of Mary Shelley's hand-written edits on the Thomas

copy

of the 1818

publication.

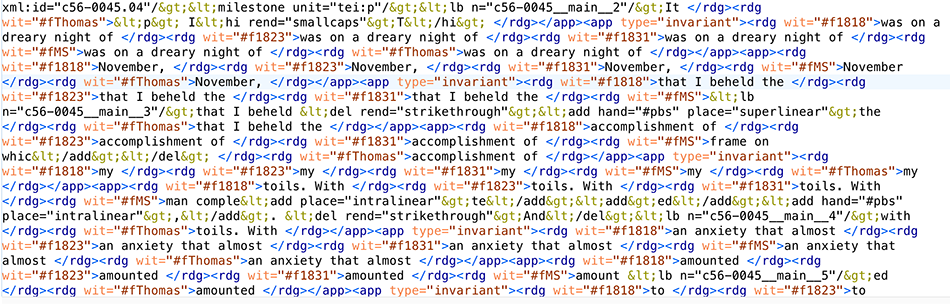

Stage two weaves these surrogate editions together and transfers information from tags that we want to preserve for the variorum. Interacting with the angle brackets as patterned strings with Python, we mask several elements from the diplomatic code of the manuscript notebooks so that they are not processed in terms of comparison but are nevertheless output to preserve their distinct information. In CollateX’s informationally-rich XML output, these tags render as flattened text with character entities replacing angle brackets so as not to introduce overlap problems with its critical apparatus.

In Stage three, we work delicately with strings that represent flattened composite of preserved tag information and representations of the text, using XSLT string-manipulation functions to construct new XML and plain text (TSV or JSON) files for stylometric and other analysis. We can then study term frequencies and, for example, where the strings associated with Percy Shelley are repeated in the later editions, and how many were preserved by 1831. We also build the stand-off Bridge in TEI for the digital variorum with its pointers to multiple editions, as discussed and modelled later in this paper.

Collation for bridge building

We had to develop an intermediary bridge format

for all of our

editions that exists specifically to serve the operational purpose of collation,

that is, the marking of moments of divergence and variation in comparable units of

text that processes only what is semantically

comparable (including the words in the novel, and whether they are marked for

insertion or deletion) and masks or ignores the portions of the documents that are

not relevant for comparison purposes (including for our purposes the elements

indicating pagination and location on a page surface). Here is a sample of the most

elaborately marked TEI we have, from the Shelley-Godwin Archive:

<zone type="main">

<line rend="center"><milestone spanTo="#c56-0045.04" unit="tei:head"/>Chapter 7<hi rend="sup"><hi rend="underline">th</hi>

</hi><anchor xml:id="c56-0045.04"></anchor></line>

<milestone unit="tei:p"></milestone>

<line rend="indent1">It was on a dreary night of November</line>

<line>that I beheld <del rend="strikethrough"><add hand="#pbs" place="superlinear">the frame on

whic</add></del> my man comple<mod>

<del rend="overwritten">at</del>

<add place="intralinear">te</add>

<add>ed</add>

</mod><add hand="#pbs" place="intralinear">,</add>. <del rend="strikethrough">And</del></line>

<line>with an anxiety that almost amount</line>

<line>ed to agony I collected instruments of life</line>

<line>around me <mod>

<del rend="strikethrough">and endeavour to</del>

<add place="superlinear">that I might</add>

</mod>

<mod>

<del rend="overwritten">e</del>

<add place="intralinear">i</add>

</mod>nfuse a</line>

<line>spark of being into the lifeless thin<mod>

<del rend="overwritten">k</del>

<add place="intralinear">g</add>

</mod></line>

<line>that lay at my feet. It was already</line>

<line>one in the morning, the rain pattered</line>

<line>dismally against the window panes, &</line>

<line>my candle was nearly burnt out, when</line>

<line>by the glimmer of the half extinguish-</line>

<line>ed light I saw the dull yellow eye of</line>

<line>the creature open.—It breathed hard,</line>

<line>and a convulsive motion agitated</line>

<line>its limbs.</line>

<milestone unit="tei:p"/>

...

</zone>

The markup above prioritizes description of lines on a manuscript notebook page surface, delineated in a zone element, and the line elements together with those indicating insertions and deletions pose us an obstacle course if we wish to attempt to compare this passage with its corresponding unit in the much simpler XML encoding we prepared for the print publications. One significant problem that we needed to solve is the way words break around the ends of lines in the notebooks. These are given hyphens only when present in the manuscript and are otherwise unmarked. Consider the challenge of comparing the sequential stream of text delineated in the code block above with the corresponding passage in our XML encoding of the 1818 edition:

<xml>

<anchor type="collate" xml:id="C10"/>

<milestone unit="chapter" type="start" n="4"/>

<head>CHAPTER IV.</head>

<p>I<hi rend="smallcaps">T</hi> was on a dreary night of November, that I beheld the

accomplishment of my toils. With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected

the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the

lifeless thing that lay at my feet. It was already one in the morning; the rain pattered

dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of

the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed

<pb xml:id="F1818_v1_110" n="098"/>hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its

limbs.</p>

...

</xml>

The code above for the pre-collation version of the 1818 edition is not written in

TEI but borrows its elements. This is an example of simple XML we

prepared specifically for the purpose of collation, reducing the documents to

concentrate on the running streamof text and its basic structural divisions. Here the paragraph is the most basic structural division, and chapter boundaries are signalled with milestone markers.

The act of reconciling these markup ecosystems required altering the structure of

the S-GA markup, to produce it in an alternative pre-collation bridge

format that matches up with elements in the encoding of the published editions,

which in this paper we will simply call 1818-style

). In the S-GA

markup the hierarchy is not especially deep, or it only becomes deep in describing

revision activities and changes of hand. These hierarchical structures do not

correspond with anything in the markup of the print-published editions, where

hierarchical depth comes from chapter, letter, and volume divisions. To make a

collatable bridge

format required alteration of each (S-GA and

1818-style) to

-

meet in the middle: share matching elements that contain and signal the sequence of text to be collated, and

-

stay apart: preserve the diversity of metadata in the S-GA markup about revisions and handshifts, and find a way to ignore or mask it from the collation process.

pre-collation bridge formats, we needed to flatten deep hierarchical structures from the

1818-styleXML documents by converting them into milestone-style signals. We want to retain the information about structural divisions, that is, paragraph, chapter, letter, and volume boundaries, and include this as data, since changes in paragraphing or chapter content are relevant to the variorum comparison of the Frankenstein editions. However, we also retain markup which does not designate the running sequence of text and basic text structure, but offers metadata about who wrote what, and whether the writing was inserted or deleted. This allows us to reconcile hierarchies that are otherwise completely at odds and nevertheless preserve their information, though we need to do another round of work to screen some of that information away from the collation process. Below is the sample passage from the Shelley-Godwin Notebooks rendered in our bridge format, designed to be comparable laterally with corresponding encoding in the 1818-style that we represented in the block above.

<xml>

<anchor type="collate" xml:id="C10"/>

<surface xmlns:mith="http://mith.umd.edu/sc/ns1#"

lrx="3847"

lry="5342"

partOf="#ox-frankenstein_volume_i"

ulx="0"

uly="0"

mith:folio="21r"

mith:shelfmark="MS. Abinger c. 56"

xml:base="ox-ms_abinger_c56/ox-ms_abinger_c56-0045.xml"

xml:id="ox-ms_abinger_c56-0045">

<graphic url="http://shelleygodwinarchive.org/images/ox/ms_abinger_c56/ms_abinger_c56-0045.jp2"/>

<zone type="main">

<lb n="c56-0045__main__1"/>

<milestone spanTo="#c56-0045.04" unit="tei:head"/>Chapter 7<hi rend="sup">

<hi rend="underline">th</hi>

</hi>

<anchor xml:id="c56-0045.04"/>

<milestone unit="tei:p"/>

<lb n="c56-0045__main__2"/>It was on a dreary night of November <lb n="c56-0045__main__3"/>that I beheld <del rend="strikethrough">

<add hand="#pbs" place="superlinear">the frame on

whic</add>

</del> my man comple<mod>

<add place="intralinear">te</add>

<add>ed</add>

</mod>

<add hand="#pbs" place="intralinear">,</add>. <del rend="strikethrough">And</del>

<lb n="c56-0045__main__4"/>with an anxiety that almost

<w ana="start"/>amount<lb n="c56-0045__main__5"/>ed<w ana="end"/> to agony I

collected instruments of life

<lb n="c56-0045__main__6"/>around me <mod>

<del rend="strikethrough">and endeavour to</del>

<add place="superlinear">that I might</add>

</mod>

<mod>

<add place="intralinear">i</add>

</mod>nfuse a <lb n="c56-0045__main__7"/>spark of being into the lifeless thin<mod>

<add place="intralinear">g</add>

</mod>

<lb n="c56-0045__main__8"/>that lay at my feet. It was already

<lb n="c56-0045__main__9"/>one in the morning, the rain pattered

<lb n="c56-0045__main__10"/>dismally against the window panes, &

<lb n="c56-0045__main__11"/>my candle was nearly burnt out, when

<lb n="c56-0045__main__12"/>by the glimmer of the half

<w ana="start"/>extinguish<lb n="c56-0045__main__13"/>ed<w ana="end"/>

light I saw the dull yellow eye of <lb n="c56-0045__main__14"/>the creature open.—It breathed hard,

<lb n="c56-0045__main__15"/>and a convulsive motion agitated

<lb n="c56-0045__main__16"/>its limbs.<milestone unit="tei:p"/>

Notice what has changed here: We not only had to flatten <line>

elements into self-closing <lb/> signals but we needed to insert <word> elements in order to unite whole words broken

around the notebook lines. We also added locational flagsor

signal beaconsas the attribute on

<lb

n="*"/>, to assist us on the other side of the collation with generating

XML pointers back to the source text: these indicate positional zones and lines on

the notebook page surfaces, so that when output that data can be kept with its

associated collation units. In these information-enriching activities, of course,

we

are doing the human work required of interchange, and we do so in the interests of

interoperability, so the automated collation process can locate the same word tokens

without interference.

The pre-collation bridge format

needs to retain certain marked

metadata from the original TEI, including for example, whose hands are at work on

the manuscript at a given moment, so we can attempt to see if a string of text

inserted by Percy Bysshe Shelley continues to be supported in the later print

publications. However, such metadata needs to be masked from the collation process

so that we are not folding it into comparison of the running streams of text that

compose each version of the novel. To deliver these pre-collation

bridge

XML files to CollateX and instruct the software collation

algorithm on how to process them, with and

around their markup, we wrote a Python script

working with its xml.dom.pulldom tool, which parses XML documents as a running

stream of text and instructs the collation process to ignore some patterns

surrounded by angle brackets, while actively collating the others.[15]

In turn, the XML output generated by CollateX itself serves as an intermediary

format, not in TEI, but containing its components in the form of critical apparatus

tagging, to hold information about the deltas of variance among the editions. The

output in XML flattens the tags we submitted into angle brackets and text, and the

shallow XML hierarchy holds only critical apparatus markup: <app>

and its children <rdg> to mark divergent branches. The complexity

of the code is such that perhaps it is nearly illegible to human eyes and might

best be rendered in a screen capture for our purposes. Here is a view of the

collation output for the sample portion of Frankenstein we have been representing:

While it may be difficult on human eyes, this code is information-rich and

tractable for the next stage of work in building up the Variorum. Due to its shallow

hierarchy combined with its embedded complexity, we might consider this output to

be

an interchange format in its own right, though we now face a challenge in processing

complex details from the source editions now signalled by the pseudo-markup of the

angle-bracket escape characters. In a way, this is a kind of database format from

which data can be extracted and repurposed from XPath string operations, but the

collation process is quite likely to break up the original tagging of

<add> or <del> because it has prioritized

the location of comparable text strings while masking

(or parsing

around) those tags. We do not treat this as an impossibility, but rather as a moment

where the most interoperable portion of the document (the text characters, as

Desmond Schmidt would point out), becomes something we need to address with

programming tools as structured data. At the time of this writing, we are working

with this output of collation to repurpose it in multiple ways:

-

as a resource for analyzing the nature and variety of revisions made to the novel over time, tracing the most frequent and most extensive changes, and their locations (as in, identifying which portions of the novel were most heavily revised over time);

-

as a resource for stylometric analysis (as for example, tracking which portions of the document contain edits by Percy Shelley, and what becomes of these variants over time in later revisions to the novel);

-

as a basis for conversion into the bridge format of the reading interface, generating pointers to the source editions.

We should clarify that these represent multiple, quite challenging processing

efforts: the same XSLT that helps to generate pointers into the original editions

will not suffice for dealing with insertions and deletions: indeed the goal is not

to reproduce the intricately detailed page imaging of the Shelley-Godwin Archive but

rather to point precisely to its pages. A different XSLT process will give us a

bridge

rendering of the notebooks with highlights and

interactions to indicate how it compares and where it

diverges from other editions, and each edition needs to be rendered

individually in a way that demonstrates its own comparability and deviation from the

others.

The reading interface for the Variorum edition will optimally make available the

combined results of our data processing, and as a starting point, we are writing

XSLT to analyze strings and locating their positions in the source documents to

construct in TEI a spinal column

for interconnecting the data on

variation. The variorum edition architecture applies pointers in a form of

stand-off parallel segmentation

, which enhances the available

models in the TEI Guidelines for stand-off collation while supporting the TEI’s

longstanding interests in both interchange and interoperability, as we discuss

below.

Crossing the bridges

We decided to build a variorum edition on the spine

of a TEI structure

that holds forks and branches and that does not set priorities of a base text that

should be preferred over any of the others. The apparatus criticus itself is to hold

a

structure of stand-off pointers that locate and link to passages in each separate

edition. Stand-off in the TEI was designed specifically to deal with non-hierarchical

structures as a conflict with its OHCO model.[16] However, if we build up from a model of critical apparatus that is already

breaking with singular hierarchy and rather expressing forks and branches, and if

we

further do not establish a single base text, we adapt the TEI tree to something more

like a graph-based model, in which the hierarchy of elements exists so that

<app> elements serve as bridges or edges that hold and connect

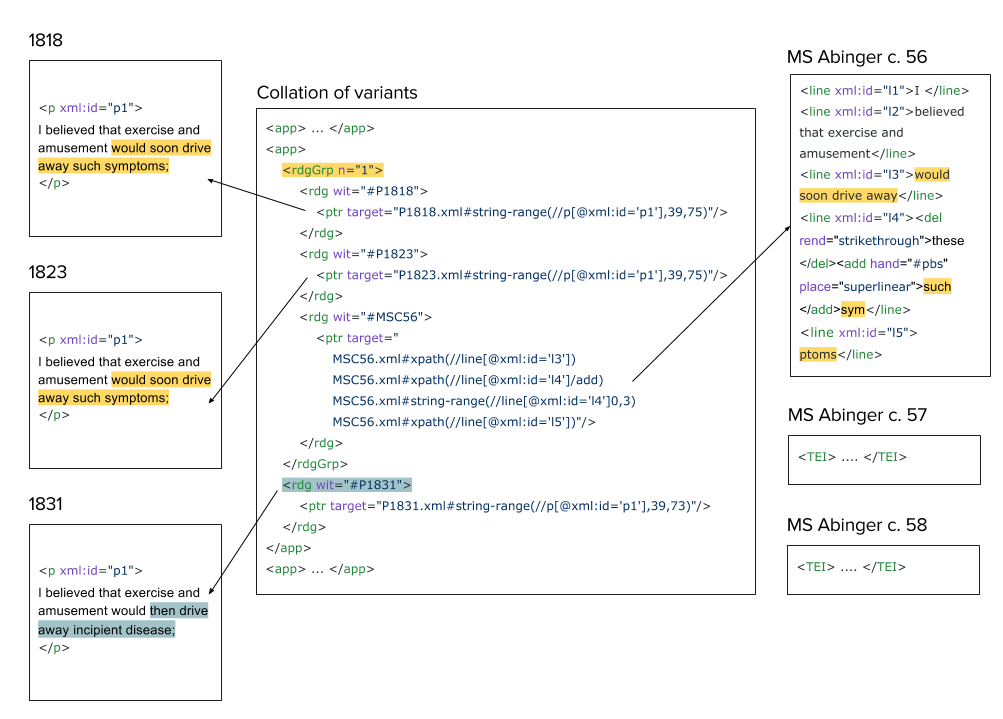

its nodes in the form of <rdg> elements (for reading witnesses).[17] The starting priority was to generate pointers from the Variorum edition

interface directly to pages like this

one in the Shelley-Godwin Archive edition of the 1816 draft manuscript

notebooks. The pointers, as modelled in the figure

below, locate not merely the pages but the specific lines we had

precisely captured in the S-GA markup prior to collation.

Variant: Sample Variant

An example variant with two different readings, showing Percy Bysshe Shelley’s hand in the ms notebook. While the print editions of 1818, 1823, and the manuscript agree (yellow reading), the print edition of 1831 introduces new text (blue reading). The pointers are expressed according to the TEI XPointer Schemes defined in Chapter 16 of the TEI Guidelines and are subject to change.

This example shows how the stand-off collation identifies variant readings between texts by grouping pointers as opposed to grouping strings of text according to the parallel segmentation technique described in Chapter 12 of the TEI Guidelines.[18] The TEI offers a stand-off method for encoding variants, called “double-end-point-attachment”, in which variants can be encoded separately from the base text by specifying the start and end point of the lemma of which they are a variant. This allows encoders to refer to overlapping areas on the base text, but despite its flexibility, this method still requires choosing a base text to which anchor variant readings, so it is not ideal for a variorum edition like ours that, by design, does not choose a base text.[19] Our approach, therefore, simply identifies variance and groups readings from multiple sources without conflating them into one document and with accommodation of multiple hierarchies.

Generating the stand-off parallel segmentation requires processing and manipulating

our multiple versions of TEI-encoded Frankenstein to

locate the addresses

of each varying point. This document is not,

however, the end of the story: the bridges that it establishes are there to be crossed.

Crossing the bridges, that is following the pointers, is not always trivial. Serious

reasons for the somewhat limited use of stand-off in TEI include the inadequate support

for resolving XPointers, as well as the risk of not finding what was expected at the

other end because of link rot

, or because the target file was – even

minimally – changed. In creating our stand-off collation, we tried to keep pointers

as

simple as possible by favoring locations expressed with XPath 1.0 over locations with

string ranges (although the latter are unavoidable on multiple occasions). Finally,

we

made use of GitHub’s ability to obtain URLs to specific versions of files, which means

that the files we point to are guaranteed not to change unexpectedly (although the

URL

itslef may rot

and return a 404, eventually)[20].

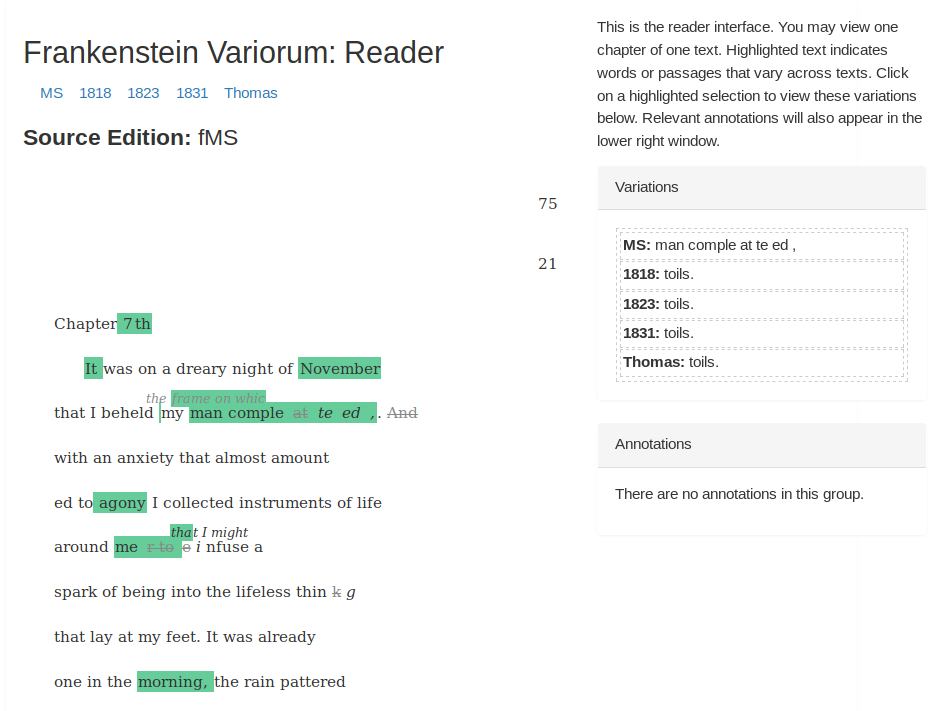

Having taken these precautions, our primary goal is building a web-based interactive variorum edition that readers can use to explore each version of the text. For example, one could start by reading the 1818 version of the novel; highlighted text would indicate the presence of a variant from another version and by clicking on it, the site visitor would be able to

-

choose which variant readings they wish to read and compare, and

-

change their current view and pivot to a different text or grouping of texts.

Prototype: An early prototype of the variorum interface

A screenshot of an early prototype of the variorum interface. The Frankenstein text shown is TEI data taken 'on the fly' from S-GA's GitHub repository. The application, morevoer, follows the pointers in the stand-off collation to highlight variants on the text and, when highlighted text is clicked, show readings from other sources on the right hand side.

Publishing the variorum is but one path that can be taken across the bridges of our collation. As we mentioned earlier, we kept in mind the richness of S-GA TEI documents, particularly regarding authorship (who wrote what) and authorial revisions. In order to follow a pointer to an S-GA document, we must process the full document; while it may seem counter-intuitive, this is an advantage because we gain access to the full context of the texts we address.[21] This would allow us, for example, to determine and indicate in the user interface whether a variant reading was part of a revision by Percy Shelley, or allows us to perform larger scale operations to track such phenomena, which could then be plotted as visualizations.

Conclusions and prospects

Though we think of hierarchical XML as a stable sustainable archiving medium, the repeated collapsing and expansion of hierarchies in our collation process makes us consider that for the viability of digital textual scholarship, ordered hierarchies of content objects might best be designed for interchange with leveling in mind, and that building with XML may be optimized when it is open to transformation. Preparing diversely encoded documents for collation challenges us to consider inconsistent and overlapping hierarchies as a tractable matter for computational alignment—where alignment becomes an organizing principle that fractures hierarchies, chunking if not atomizing them at the level of the smallest meaningfully sharable semantic features.

We hope that our efforts on this project will yield new examples and

enhancement of Chapter 12 in the TEI Guidelines on the Critical Apparatus, to develop a

model of stand-off annotation that does not require choosing a base text. However,

the

perspective we have gained on enhancing interchange for the purposes of interoperation

may have larger ramifications in the ongoing discussion of graph-based models and

their

application to the TEI.[22] For much the same reasons that motivate us, Jeffrey C. Witt designed the

Scholarly Commentaries and Texts Archive, to transform digital silo

projects into a network of data.[23] While that project seeks a definitive language of interchange for medieval

scholastic textual data, on a smaller scale trained on multiple divergent encodings

of

the same famous novel, we have negotiated interchangeability by cutting across

individual text hierarchies to emphasize lateral connections and commonalities—making

a

new TEI whose hierarchy serves as a stand-off spine

or

switchboard

permitting comparison and sharing of common data. Our

goal of pointing to aligned data required us to locate the interchangeable structural

markers in our source documents, and enhances interoperation by making it possible

for

software to parse the comparable with the incomparable, the similar with the divergent.

Ultimately, we want to promote the long-term sustenance of digital editions by building

bridges that permit monumental but isolated projects to be interchangeable rather

than

having to remake them from the ground up. Building ramps for interchangeability is

an

investment in interoperability as well, specifically for producing the comparative

views

afforded by collation.

[1] View Andrews’s keynote Freeing Our Texts

from their (Digital Tool)chains

.

[2] Elli Mylonas, Allen Renear, The Text Encoding Initiative at 10: Not

Just an Interchange Format Anymore – But a New Research

Community

, Computers and the Humanities 33:1-2 (April 1999) 1-9;

3.

[3] See for example, P. M. W.

Robinson, The Collation and Textual Criticism of

Icelandic Manuscripts

,

Literary and Linguistic

Computing, Volume 4, Issue 2, 1 January 1989,

99–105, doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/4.2.99; Dekker, Ronald

Haentjens, Dirk van Hulle, Gregor Middell, Vincent Neyt, and

Joris van Zundert, Computer-supported collation of modern

manuscripts: CollateX and the Beckett Digital Manuscript

Project

,

DSH: Digital Scholarship in the

Humanities Volume 30, Issue 3, 1 September 2015,

452–470, doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqu007; Eggert, Paul,

The reader-oriented scholarly edition

Digital Scholarship in the

Humanities, Volume 31, Issue 4, 1 December 2016,

797–810, doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqw043; and Holmes, Martin,

Whatever happened to interchange?

Digital Scholarship in the

Humanities, Volume 32, Issue suppl_1, 1 April

2017, 163–168, doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqw048.

[4] See Gerrit

Brüning, Katrin Henzel, and Dietmar Pravida, Multiple Encoding in

Genetic Editions: The Case of ‘Faust’

, Journal of the Text

Encoding Initiative (4: March 2013).

[5] Desmond Schmidt, Towards an Interoperable Digital Scholarly Edition

, Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative Issue, November 2014.

[6] Where Schmidt comments on the ability of Google Docs to represent a Word document, we recall plenty of friction between the two formats, and while it may be marvellous that web browsers can interpret HTML, they do not all interpret the specs in the same way, and as standards for CSS and JavaScript change, these methods for presentation are not always consistently experienced from browser to browser.

[8] See the documentation, CollateX – Software for Collating Textual

Sources

. Another inspiration for the bridging concept are the

visualizations in Haentjens Dekker, Ronald, and David J. Birnbaum, “It’s more than just

overlap: Text As Graph,” In Proceedings of Balisage:

The Markup Conference 2017, Balisage Series on Markup

Technologies, vol. 19 (2017).. The authors

conceptualize an ideal model of texts in a graph structure organized primarily

by their semantic sequencing and in which structural features are a matter of

descriptive annotation rather than elemental hierarchy.

[9] The Frankenstein Variorum project involves a collaboration of researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH), and GitHub repository at https://pghfrankenstein.github.io/Pittsburgh_Frankenstein/. At the time of this writing the web development for the variorum edition interface is under construction.

[10] Curran, Stuart and Jack Lynch, Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. The Pennsylvania Electronic Edition. Est. 1994. See a representative page at http://knarf.english.upenn.edu/Colv1/f1101.html.

[11] The Shelley-Godwin Archive’s edition of the manuscript notebooks of Frankenstein builds on decades of intensive scholarly research to create TEI diplomatic encoding: http://shelleygodwinarchive.org/contents/frankenstein/.

[12] This is known as the Thomas copy

because Mary Shelley left the

1818 publication containing her handwritten insertions, deletions, and comments

with her friend Mrs. Thomas before leaving Italy for England in 1823, following

Percy Shelley’s death in Lerici. The edits may have been entered at any time

between 1818 and 1823, and they are of interest because they indicate at an

early stage that Mary Shelley wanted to alter many passages in her novel, and

was continuing to experiment with the characterization of Victor and the

Creature. But they also indicate a point of divergence, since she did not have

access to these edits in revising the novel for its 1831 publication. A key

motivation for collating these editions is to attempt to compare the novel as it

was being revised soon after its first publication (whose bicentennial we

celebrate in 2018) with its later incarnation in the traditionally widely read

1831 edition. Another is discovering just how different the 1816 draft notebooks

are from the later texts. Scholars over the past forty years have oscillated

between the 1831 and 1818 editions as the preferred

texts, but

there is really no single canonical version of this novel, and for that reason

our Variorum edition does not indicate a standard base text

,

which is still unusual in representing scholarly editions.

[13] Barbara Bordalejo, ed. Darwin Online. See for example the illumination of variant passages in The Origin of Species here: http://darwin-online.org.uk/Variorum/1859/1859-1-dns.html

[14] These hierarchical issues provided an application for Piez’s invented LMNL

sawtooth

syntax to highlight overlap as semantically

important to the novel; see Wendell Piez, Hierarchies within range space: From LMNL to

OHCO,

Balisage: The Markup Conference Proceedings (2014):

https://www.balisage.net/Proceedings/vol13/html/Piez01/BalisageVol13-Piez01.html

[15] See the xml.dom.pulldom documentation here: https://docs.python.org/3/library/xml.dom.pulldom.html. The Python script is available on our GitHub repository here: https://github.com/PghFrankenstein/Pittsburgh_Frankenstein/blob/master/collateXPrep/allWitness_collation_to_tei.py.

[17] For a visual example, a group of Pitt-Greensburg students led by Nicole Lottig and Brooke Stewart experimented with a network analysis of editions of Emily Dickinson's Fascicle 16 poems that share the most variant readings, and to see which most closely resembled one another. See their network visualization and explanation here: http://dickinson16.newtfire.org/16/networkAnalysis.html

[18] See especially the TEI P5 Guidelines, 12.2.3 and 12.2.4: http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/TC.html#TCAPPS

[19] For a related example, see Viglianti, R. Music and Words: reconciling libretto and score editions in the digital medium. “Ei, dem alten Herrn zoll’ ich Achtung gern’”, ed. Kristina Richts and Peter Stadler, 2016, 727-755.

[20] See Cayless, Hugh A., and Adam Soroka, “On Implementing string-range() for TEI,” Proceedings of Balisage: The Markup Conference 2010., Balisage Series on Markup Technologies, vol. 5 (2010)

[21] For a related discussion of addressability and textuality see Michael Witmore,

Text: A Massively Addressable Object

, Debates in the Digital Humanities

2012.

[22] For reflection on pertinent examples, see Hugh A. Cayless, Rebooting TEI

Pointers

, Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative, Issue 6,

December 2013 and his blog posting, Graphs, Trees, and Streams: The TEI Data Model

, Duke

Collaboratory for Classics Computing (DC3), 26 August 2013. Cayless’s

work on developing pointer specifications to enhance TEI expression beyond

inline embedded markup is now part of the TEI Guidelines Chapter 16: Linking, Segmentation, and Alignment.

[23] See Jeffrey C. Witt’s recorded presentation, Texts as Networks: The

Promise and Challenge of Publishing Humanities Texts as Open Data

Networks

for the Conference on Philosophy and History of Open

Science at the University of Helsinki, 30 November - 1 December 2016,

and on better supporting interoperability in particular see his Creating an aggregated dataset from distributed

sources

, a report from the Linked Data and the

Medieval Scholastic Tradition

workshop held at the University of

Basel in August 17-19, 2016.