What is PMC?

PubMed Central PMC01 is the U.S. National Institutes of Health's free digital archive of full-text biomedical and life sciences journal literature. Content is stored in XML at the article level. and is displayed dynamically from the archival XML each time that a user retrieves an article. Publishers submit XML, images, and supplemental files for their articles, the text is converted to a common JATS XML, and the files are loaded to a database for display and distribution.

PMC is also the repository that supports the NIH Public Access Policy NIH01 and the public access policies of other Federal agencies such as CDC, EPA, FDA, NASA, NIST, and the VA as a result of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy memo on expanding public access to the results of Federally funded research Obama01.

PubMed Central was started in 1999 to allow free full-text access to journal articles. Participation by journals is voluntary. From the beginning there has always been a requirement that participating journals provide their content to NCBI marked up in some "reasonable" SGML or XML format Beck01 along with the highest-resolution images available, PDF files (if available), and all supplementary material. Complete details on the PMC's file requirements are available PMC02.

PMC Ingest Workflow

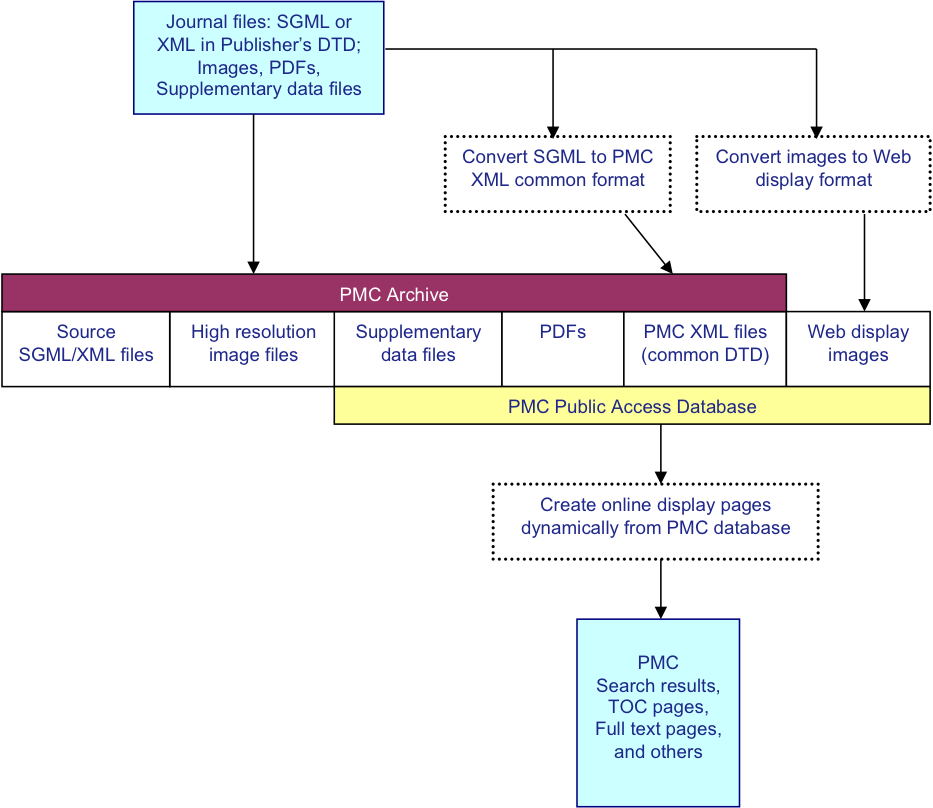

The PMC processing model Beck01 and text processing philosophy Kelly01 have been discussed in detail previously. Briefly it is diagrammed in Fig. 1. For each article, we receive a set of files that includes the text in SGML or XML, the highest resolution figures available, a PDF file if one has been created for the article, and any supplementary material or supporting data. The text is converted to the current version of the NISO Archiving and Interchange Tag Set JATS01 (currently JATS 1.1 Archiving and Interchange), and the images are converted to a web-friendly format. The source SGML or XML, original images, supplementary data files, PDFs, and NLM XML files are stored in the archive. Articles are rendered online using the NLM/JATS XML, PDFs, supplementary data files, and the web-friendly images.

Fig. 1: PMC Processing Model

PMC Policies and Operations

General Philosophy

The goal of PMC is to have the highest quality journal information available for the public. This includes having high quality journals in the collection and ensuring that the content in PMC reflects the published record accurately.

Evaluation

Participation in PMC is voluntary for publishers, but there is a two-part evaluation for each new title. First, is the scientific or content evaluation. Journals that are not being indexed for MEDLINE NLM01 must be reviewed for by NLM staff to ensure that the journal includes content that should be added to the NLM collection. There are minimum content requirements (50+ articles), and the editorial policies, editorial board, and published articles are all reviewed.

Next the journal must go through a technical evaluation to "be sure that the journal can routinely supply files of sufficient quality to generate complete and accurate articles online without the need for human action to correct errors or omissions in the data." PMC02

For the evaluation, a journal supplies a sample set of articles (at least 50). These articles are put through a series of automated and human checks to ensure that the XML is valid and that it accurately represents the article content. There is a set of "Minimum Data Requirements" that must be met before the evaluation proceeds to the more human-intense content accuracy checking PMC03.

This two-part evaluation is set up to try to a) keep the quality of content being submitted to PMC to a high standard, and b) ensure that publishers (or their tagging vendors have the technical ability to delivery content to PMC on an ongoing basis.

QA

All content that is ingested into PMC goes through some amount of quality checking. This has been detailed in Kelly01. The PMC production team is made up of a set of Journal Managers who are responsible for the processing and checking of content for the journal titles that are assigned to them. We use a combination of automated processing checks and manual checking of articles to help. For each title, a certain percentage of articles must be checked by eye against a "version of record", which is either the publisher's PDF, HTML, or print version of the article. Titles with more problems get more checking. Problems are fed back to the publisher for corrections and resubmission of the content. This is a laborious and expensive process. But XML tools―well-formedness and validity checks― are not able to reveal inaccurate content in the article Bauman01

PMC Staff

PMC is supported by three groups of people: PMC Production, Literature Developers, and the XML Conversion team.

The PMC Production team is a group of 18 that includes the Journal Managers, who are responsible for managing the flow of content from providers and the QA of that content. The production team also includes people who manage the Scientific Evaluation of journals with Library Operation, perform the Technical Evaluation of new titles, and handle all of the publisher agreements.

The Literature Development team supports PMC and other literature projects at NCBI including the NCBI Bookshelf and the NIH Manuscript submission system.

The third group is the XML Conversion team. This group writes and maintains the XSL transforms that are used to normalize all of the submitted text to the common JATS format. This group also supports the Production group diagnosing problems with the ingest of content and solving XML tagging questions and problems from the Journal Managers and publishers.

The Challenges

Classic Challenges

Even though journals go through the Technical Evaluation, problems do show up when a title has been "moved to production". Generally these include things that can be expected:

-

A new structure has been added to the journal or shows up in an article- such as math or a complex table - that the provider is not used to tagging.

-

Special article types - especially those that require <related-article> links to other articles. These include Erratta, Retractions, Expressions of Concern, etc.

-

Experienced tagging staff moves on or goes on vacation leaving the replacements to figure things out on their own.

-

The journal changes tagging vendors or article models and just starts sending new content to PMC.

New Economy Challenges

There have been a lot of changes to journal publishing since PMC started in 2000. At that time, most journals were printing regular issues and worrying about the "electronic" or online copy once the print issue was finished. Because the electronic journal files were an afterthought, this led to a number of quality problems in the electronic files. This has changed significantly with many titles creating print and electronic articles from the same source - which gives us a general rise in the quality of tagging.

But the XML tagging is not where we are seeing problems here. The availability of online publishing complicates things in other ways. One of the obvious things that can change is that articles no longer have to wait to be put into an issue and printed to be "published"1 Articles an be posted online immediately upon completion and may or may not be collected into print issues later. The issues that we see are when publishers want to maintain their traditional way of referring to their articles using old print issue citations2 but they are not publishing in traditional issues. They try to force issue issue information or even print publication dates onto their articles rather than just using an article level identifier such as a DOIDOI1.

One example of this is when the online articles and PDFs are made from the article XML. Because the online publication uses a DOI as it's identifier (and may use the DOI suffix as an <elocation-id>), the online article can be referenced by the DOI. The PDF made from the XML is assigned page numbers of 1-n. This would mean that every article in volume 55 would have a citation of "J Example. 55:1", which is useless as a reference.

Usually, these decisions are made high up at the publisher by "old-timers" who feel a need to use the traditional citations but are forced into using new publishing methods. PMC staff must educate/negotiate/cajole journal staff to see why this is not a wise practice and help the staff explain it to their bosses.

PMC was created to provide access to medical journal articles and was a keystone in the Open Access Publishing movement Bethesda01. An unintended consequence of the Open Access movement is the rise of predatory publishers. Predatory publishing is described as "an exploitative open-access publishing business model that involves charging publication fees to authors without providing the editorial and publishing services associated with legitimate journals"Wiki1

Predatory publishers have a much more valuable product if they can get their articles into PubMed. Because PMC sends citations to PubMed for journals who are not already in PubMed, predatory publishers work very hard to get their content into PMC and then into PubMed. This led to the development of the stringent publisher review and journal scientific review described above.

Another change in journal publishing that has an effect on PMC has been the trend toward versions of articles. There are two areas that we have to deal with.

Traditionally when a problem or error is discovered in a published article, the publisher publishes a Correction or Erratum. The Erratum is published as a separate article that describes that the problem is and references the original article.

Now, with predominantly electronic publishing, publishers want to silently correct articles in place. This goes against NLM policyNLM02 as is not generally considered to be a good ideaGautam01. A similar situation arises for articles that would traditionally be retracted. When there are serious enough problems with the publcation of the article or the research underlying the article, the publisher would "retract" the article. That is, they would publish a short separate article that describe the problem(s) with the publication or research and reference the original "retracted" article.

In PMC, retractions and corrections that have <related-article> links that refer to the article being corrected or retracted. We can put notices on the original articles and build links forward in time to the correction and retraction notices.

Now it is possible for publishers to silently update articles to correct them or even to remove them from their own websites. This leaves a hole in the published record. Articles can not disappear from PMC. When it is discovered that an article has changed (sometimes the publisher sends a new copy of the XML) or disappeared, PMC Journal Managers must chase down and encourage publishers to publish corrections and retractions.

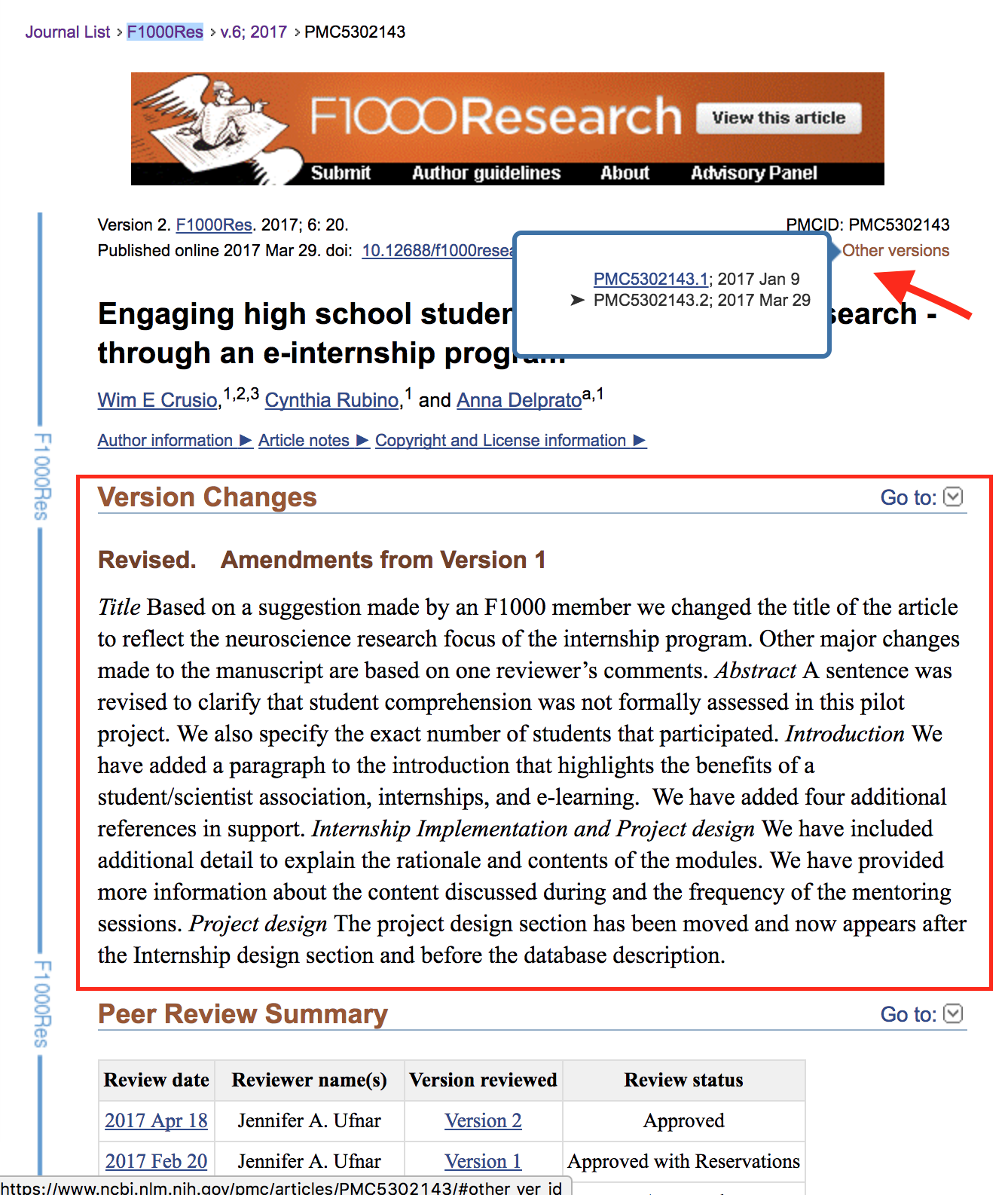

Obviously, this will change. Updating or changing articles in place only makes sense, but it must be done in a way that every version of the article is available and the changes between versions are listed. There are several PMC-participating publishers sending articles in this way. A good example is F1000 Research https://f1000research.com/. This journal has an open peer review, which means that the peer reviews are included with the articles. Each updated version also includes descriptions of the changes between versions.

To include F100 Research in PMC, we had to handle the peer reviews, the version notes, and multiple versions of articles. See this article in PMC: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5302143/.

Fig. 2: F1000 Research Article

Descriptions of the changes between versions are in the red box. Links to the peer reviews (which are at the bottom of the article) are below the box. Links to other versions are available in the upper right corner by the red arrow.

Scale Challenges

PMC is now 17 years old. We have a lot of automated processes set up for ingest and processing of submitted files. This works great for submissions that have no problem. But investigating and diagnosing submissions that fail are still manual tasks that take an experienced Journal Manager.

Because we cannot keep expanding the staff as the amount of content that we handle each week increases, we need to find ways to get more from our tools. Currently ingest batches that process cleanly show up on a Journal Manager's list for QA. This has been described earlierKelly01. Ingest batches that fail need to be diagnosed, and the problems need to be reported back to the submitter or to the PMC XML Conversion team for work.

There are many things that can be wrong, from the very basic - XML files not well-formed or not valid - to the more obscure - a valid submission is converting to an invalid PMC XML file. Currently we have a project to automatically send feedback for batches that we know are not PMC's problem. This would include the not well formed and not valid XML, image files that are not images, or files that are referenced from the XML that have not been supplied in the package.

The biggest challenge for this project is classifying all of the errors that our conversion generate to see if we can decide without human input whether they are source problems or processing problems. Those that cannot be classified will have to be diagnosed by a human, but this work should reduce the routine reporting of basic problems to publishers.

Conclusion

The challenges with PMC are not about the XML. Like most other XML projects, the XML is the easy part.

PMC has been successful because we have a solid group of people who work on policy, publisher relations, Quality Assurance, development, and finally XML conversion who work together toword a high quality and solid archive of articles.

References

[PMC01] PubMed Central, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/.

[NIH01] NIH Public Access Policy, https://publicaccess.nih.gov/.

[Obama01] White House OSTP memo on Public Access, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2013/02/22/expanding-public-access-results-federally-funded-research.

[Beck01] Beck, Jeff. “Report from the Field: PubMed Central, an XML-based Archive of Life Sciences Journal Articles.” Presented at International Symposium on XML for the Long Haul: Issues in the Long-term Preservation of XML, Montréal, Canada, August 2, 2010. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on XML for the Long Haul: Issues in the Long-term Preservation of XML. Balisage Series on Markup Technologies, vol. 6 (2010). doi:https://doi.org/10.4242/BalisageVol6.Beck01.

[PMC02] How to Join PMC, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/about/pubinfo.html.

[JATS01] NISO Journal Article Tag Suite (JATS), http://jats.nlm.nih.gov/archiving/.

[Kelly01] Kelly, Christopher, and Jeff Beck. “Quality Control of PMC Content: A Case Study.” Presented at International Symposium on Quality Assurance and Quality Control in XML, Montréal, Canada, August 6, 2012. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Quality Assurance and Quality Control in XML. Balisage Series on Markup Technologies, vol. 9 (2012). doi:https://doi.org/10.4242/BalisageVol9.Beck01.

[NLM01] FAQ: Journal Selection for MEDLINE Indexing at NLM, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/j_sel_faq.html.

[PMC03] Minimum Requirements for PMC Data Evaluation Submissi, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/pub/min_requirements/.

[Bauman01] Bauman, Syd. (2010) "The 4 Levels of XML Rectitude", Balisage 2010, poster. http://www.wwp.northeastern.edu/outreach/seminars/uvic_advanced_2015/venue/XML_rectitude.pdf.

[DOI1] The DOI System, https://www.doi.org.

[Bethesda01] Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing, http://legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/bethesda.htm.

[Wiki1] Predatory open access publishing, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Predatory_open_access_publishing.

[Beal1] Beall, J. (2012). "Predatory publishers are corrupting open access". Nature. 489 (7415): 179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/489179a.

[NLM02] Fact Sheet: Errata, Retractions, and Other Linked Citations in PubMed, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/errata.html.

[Gautam01] Allahbadia GN. Why Correcting the Literature with Errata and Retractions is Good Medical Practice? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India. 2014;64(6):377-380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-014-0643-z.

1 What "published" means is, surprisingly, a much discussed topic. My opinion is that an article is first published when it is first made available to the public in a form approved by the publisher. That is, if an article is written and posted on an author's website, she has published it. If she then submits it to the Journal of Examples, who does a peer review and copyediting and makes general suggestions for the improvement of the paper and then posts it on its website on August 1, 2017, then the article is published by the owner of the Journal of Examples on August 1, 2017. If they then print it in a Fall-Winter 2017 issue on November 22, 2017, the article has still been "published" on August 17, 2017.

2 The article "citation" like "Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Nov 21; 92(24): 11086–11090." includes information about the article so that the article can be located. This example includes the journal title (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.), the publication date (1995 Nov 21), volume (92), issue number (24), and page range (11086–11090). The citation can be thought of as an alternative name for the article. For journals that use continuous pagination through the volume, the citation can be as simple as journal title, volume, and first page, i.e. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 92:11086