Introduction and Background

Some discoveries, including quite important discoveries such as penicillin, are made by accident. It can be the case that when looking for a solution to one problem, we stumble upon a solution to another problem. This is one of those cases. Our objective was to find a way to represent change to structure, and this turned out to provide a useful representation for overlapping hierarchy, but with the advantage that other changes could also be represented.

Jeni Tennison says in one of her excellent blogs, "Overlap is arguably the main remaining problem area for markup technologists." [1]. She points out that this is not only an issue for academics looking at poetry and historical documents, but is also an issue in managing change to structured documents. The example she cites is legislation which is amended over time where the authors are not concerned about changes to structure, their primary interest is in the textual changes.

There are a number of different approaches to this problem, and some excellent reviews of the advantages and disadvantages of the approaches [2] [3] [4] [5]. Our own goal is to represent changes to documents, such as versions of documents over a period of time as they are amended, and to represent them in a way that is easy to process. This reflects the classic advantage of XML, where content can be re-purposed to meet different needs. If the document can be re-purposed, then we need to be able to re-purpose changes also, and this means changes need to be represented in way that is easy to process.

Ignoring for the moment changes to attributes, most changes can be represented by the addition and deletion of elements and their content. Additionally, we need to be able to mark segments of text that are either added or deleted. This approach allows us to represent any change, although not always in an optimal way. For example, in the extreme, the deletion of the 'old' document and addition of the 'new' document correctly represents the changes, but not in a very useful way. This leads to the observation that by duplicating content it is always possible to represent a change in a structured document. The problem is that we do not wish to duplicate content because this appears to the user as a change to the content, whereas in practice the only change may be to the structural markup around that content. This leads to the need to represent the addition, deletion, and overlapping of structural elements representing hierarchy.

The TEI format [6] has powerful, though complex, ways of representing different hierarchies, and also variants of text within a document. The goal is to provide rich semantic information about the document, representing all of this information in a single place. Using this semantically rich representation, it would be possible to generate all the different variants of the document, including variants of the text and variants of the hierarchy. When we are considering change, it is essentially all these different variants that we use as a starting point. Therfore in this respect our goal is very similar to, but not quite the same as, the goal of the TEI format. As our starting point is a set of document variants, it is natural that we clearly identify each of these source variants in the single merged document. We therefore always make a very precise differentiation between two overlapping structures, because these are considered to have come from different source documents.

The inherent model that we adopt here, i.e. one that addresses the representation of variants of the whole document, is important because it does differ from a model where the desire is to represent variants in structure within a document. The latter model can lead to a very large number of whole document variants, and our model is not well suited to a large number of variants because the attribute values representing the variants become long and therefore difficult to manage. Our model addresses primarily overlap in the context of change to a document and is not intended as a solution to all overlap representation problems.

Although TEI has these mechanisms, most XML document formats, such as DITA[7] or DocBook[8], do not and would therefore benefit from a way of representing overlap. In these formats, overlap representation is needed in order to better represent change. There is a clear advantage to having a standard way to enhance an existing schema with change and overlap representation because structured document editing applications then need to understand only one way of handling this. Schmidt [9] suggests that a good way to manage documents that have overlapping hierarchy is to split them into separate documents and merge them as needed, though this idea does not seem to have gained a significant following.

There is another distinguishing feature of this solution. In other solutions for representing overlap, identifier attributes (which may or may not be strictly of type xml:id) are often used to indicate which fragments are part of the same element, but with this solution there is no such use of identifier attributes. The problem with using identifier attribtues is that it is difficult to denote a fragment that is part of two separate hierarchies because only one identifier attribute can be present on each element. The identifier attribute could contain a list of identifiers but this does lead to make it more difficult to process.

The representation described here is pure XML. As such, standard XML processing tools such as XSLT and XQuery can be used to process it. Each of the original document variants can be extracted: this was our primary goal and is an important feature. We have verified that it is quite simple in XSLT to extract a single version, and it is simple to determine the ancestors of a particular element or piece of text. We are currently researching alternative types of processing. One XSLT approach shows particular promise for processing n-way comparison results. This uses a template that employs sibling recursion and XSLT 3.0 maps, the maps keep track of the state of each tree using an extension to the principle of a common stack.

There are validation rules, which we express in Schematron, for this representation. Validation against the original schema of the source documents would need to be done by extracting each version and validating it. In other words, we can assert that the representation is correct if the Schematron rules are passed and if we can extract each of the original documents correctly, i.e. the extracted document is deep equal to the original.

How Content Duplication Represents Any Change

Our starting point was an existing solution (a delta format) for representing change to elements, attributes and text in XML documents.[1] Any change could be represented, but changes to structure required some duplication of content. For example, two paragraphs (denoted A and B) might be:

<p>The quick brown fox.</p>

and

<p>The <s>quick</s> brown fox.</p>

This is a change only to the XML tag structure, the textual content is unchanged. However, we can represent the change by deleting the word ‘quick’ and adding the element

<s>quick</s>This is a perfectly valid representation of the change, but it implies that there has been deletion and addition and thus that the text has changed. This is shown below. The dx attribute indicates the documents in which the element and its content were present. The deltaxml:textGroup and deltaxml:text elements are wrappers introduced to delineate the word that has been deleted. We need the wrapper as a container for the dx attribute that applies to the text. The reason for the double wrapper here is that there may be more than one variant of the text, so more than one deltaxml:text element, and it is then useful to have these grouped in the outer deltaxml:textGroup for easier processing.

<p dx="A,B">The

<deltaxml:textGroup dx="A">

<deltaxml:text dx="A">quick</deltaxml:text>

</deltaxml:textGroup>

<s dx="B">quick</s>

brown fox.

</p>

It would be preferable if we could represent this change without implying change to the content. This is discussed in the next section.

Representing Structural Change without Content Duplication

In order to avoid duplication of content, we need to distinguish between the element tag and its content so that we can make assertions about the tag and content separately and independently.

As a starting point, we can add an attribute to an element to indicate whether or not this element was present in a particular variant of the document. If the element was present, then the implication is that both the tag and the contents were present. In the above situation, we want to indicate that the content, i.e. the word 'quick', was present in two versions, but the tag, i.e. the <s>, was only present in one version. We can take a simple approach to this and add an additional attribute with this information.

<p dx=”A,B” dxTag=”A,B”>The <s dx=”A,B” dxTag=”B”>quick</s> brown fox.</p>

Here, the dx attributes tells us the documents in which the element (and its content) were present, as described above. But now the dxTag attribute tells us a bit more: whether or not the tag itself was present. So where the document identifiers are the same in both the dx attribute and the dxTag attribute, the element and its content were present. Where we see dx='A,B' and dxTag='B' we can deduce that the tag was present only in B. This means that A contained ‘quick’ and B contained ‘<s>quick</s>’.

We can optimize this a little by omiting the dxTag attribute if its value is the same as the dx value. Therefore we get:

<p dx=”A,B”>The <s dx=”A,B” dxTag=”B”>quick</s> brown fox.</p>

This is a simple representation of a simple change. We can make an adjustment to this to represent, for example, a change from <i> in document A to <s> in document B as follows:

<p dx=”A,B”>The <i dx=”A,B” dxTag=”A”><s dx=”A,B” dxTag=”B”>quick</s></i> brown fox.</p>

We can now introduce some overlap and see how the principles above are extended. When overlap occurs, in order to avoid duplicating content, we need to split some of the elements into fragments - this is the approach that Jeni Tennison calls 'fragmentation'. When we fragment an element, then clearly one original element becomes two or more fragments. The dxTag attribute refers to the whole tag, so we need to extend this to represent the start and the end. To achieve this we have dxTagStart and dxTagEnd so that we clearly distinguish between the start fragment and the end fragment. In more complex situations where an element is split into more than two fragments, we also introduce dxTagMiddle for any fragement betwen the start and end fragments.

This is an example of simple overlap:

<p>The quick brown fox. It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

<p>The quick brown fox.</p><p> It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

This is represented as:

<p dxTagStart="A" dxTag="B" dx="A,B">The quick brown fox.</p> <p dxTagEnd="A" dxTag="B" dx="A,B"> It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

This shows two <p> elements, and for the B document each of these represents a complete element, denoted by dxTag="B". For the A document, the two <p> elements are fragements and so the first is identified by dxTagStart="A" and the second one by dxTagEnd="A". This is an unambiguous representation that requires no duplication of textual content. The astute observer may comment that the leading space in the second paragraph of the B document would probably have been deleted. Proper handling of whitespace is a consumer of considerable time and effort in XML document processing. This type of change could be represented but it complicates the story so is ignored for this example.

We can now consider an example of double overlap, where text is moved from one paragraph to another:

<p>The quick brown fox. It jumped over the lazy dog.</p><p> Yes!</p>

<p>The quick brown fox.</p><p> It jumped over the lazy dog. Yes!</p>

This is represented as:

<p dxTagStart="A" dxTag="B" dx="A,B">The quick brown fox.</p> <p dxTagEnd="A" dxTagStart="B" dx="A,B"> It jumped over the lazy dog.</p> <p dxTag="A" dxTagEnd="B" dx="A,B"> Yes!</p>

This shows three <p> elements, all of which are fragments in at least one document. In the B document the first of these represents a complete element, denoted by dxTag="B". The last two <p> elements are fragments and so the first is identified by dxTagStart="B" and the second one by dxTagEnd="B". This mechanism will scale to any level of complexity, for example three or more overlapping hierarchies. As overlap increases, so does the fragmentation and therefore the complexity of the result.

Although there is not time to explore this more fully in this paper, it would certainly be interesting to determine how easy it is to perform queries on this structure such as, "find all the paragraphs containing both the word 'fox' and the word 'dog'" and have this return just the A document because in the B document these words are in different paragraphs.

We can now look at a larger example including a change. We will for the example ignore white space changes. The A document is:

<book>

<p>

<seg>Scorn not the sonnet;</seg>

<seg>critic, you have frowned, Mindless of its just honours;</seg>

<seg>with this key SHAKESPEARE unlocked his heart;</seg>

<seg>the melody Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch's wound.</seg>

</p>

</book>

And the second, B, document is as follows:

<book>

<l>Scorn not the sonnet; critic, you have frowned,</l>

<l>Mindless of its just honours; with this key</l>

<l>Shakespeare unlocked his heart; the melody</l>

<l>Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch's wound.</l>

</book>

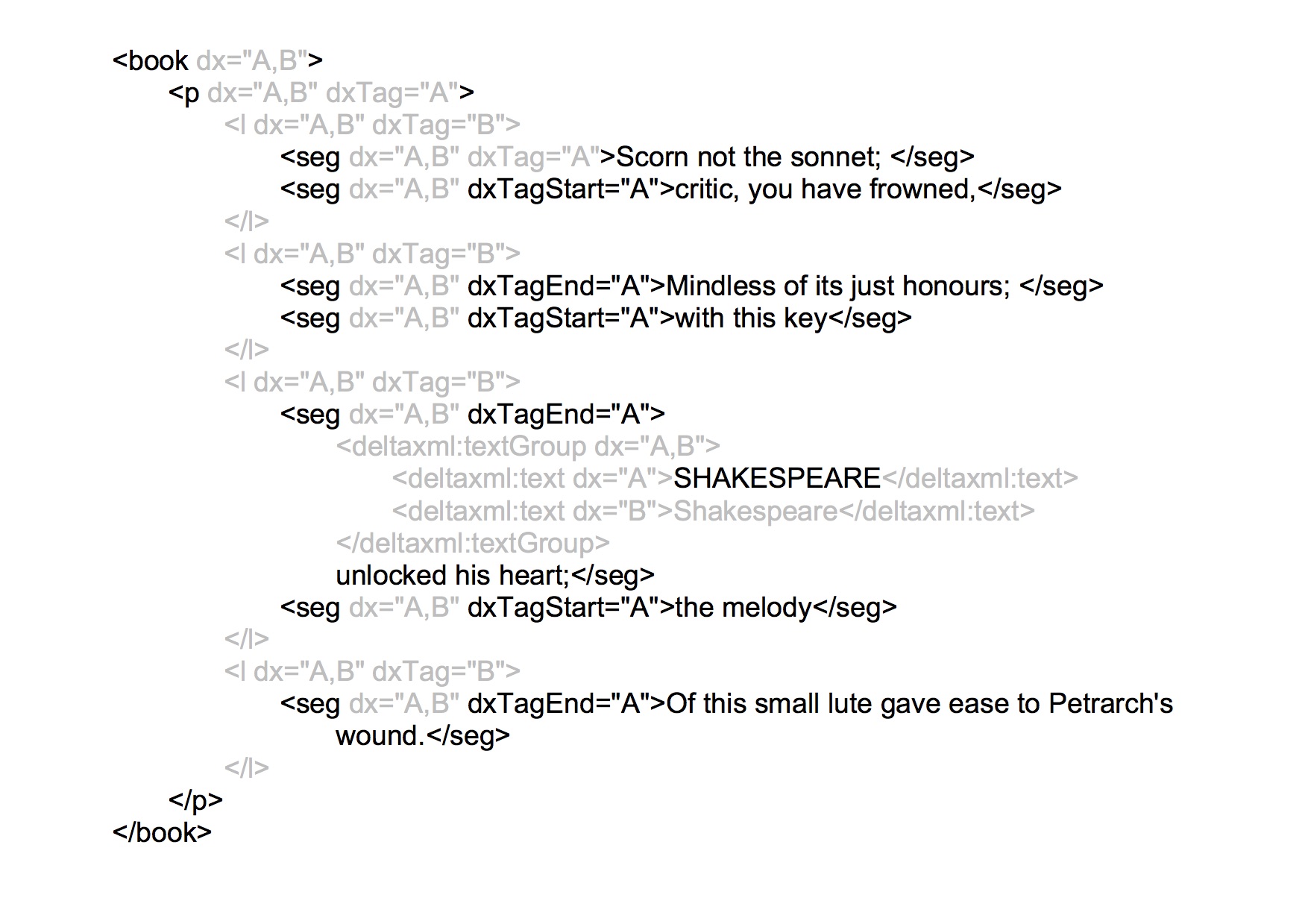

There are different representations that we can generate for this depending on how we decide to nest the fragments. For example, if we generally nest the <seg> elements inside the <l> elements, we get this result:

<book dx="A,B">

<p dx="A,B" dxTag="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTag="B">

<seg dx="A,B" dxTag="A">Scorn not the sonnet; </seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagStart="A">critic, you have frowned,</seg>

</l>

<l dx="A,B" dxTag="B">

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="A">Mindless of its just honours; </seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagStart="A">with this key</seg>

</l>

<l dx="A,B" dxTag="B">

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="A">

<deltaxml:textGroup dx="A,B">

<deltaxml:text dx="A">SHAKESPEARE</deltaxml:text>

<deltaxml:text dx="B">Shakespeare</deltaxml:text>

</deltaxml:textGroup> unlocked his heart;</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagStart="A">the melody</seg>

</l>

<l dx="A,B" dxTag="B">

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="A">Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch's

wound.</seg>

</l>

</p>

</book>

It is instructive to visualize this structure as shown below. Here we are looking

at

it primarily as document A, so the tags and text that belong only to B have been greyed

out. This is to visualize more clearly the A structure. Some of the <seg> elements

are still split so these would need to be merged in order to get back to the original

A

document, although the basic original structure of A is apparent.

This visualization illustrates the very simple nature of this approach. The attributes we are adding provide information about an element, specifically for each variant the attributes tell us which of the following is true:

-

The tag and its content are present in this variant and the element is not fragmented

-

The tag and its content are present in this variant and the element is fragmented, so this is the start, the end or a middle fragment

-

The content is present in this variant but not the tag

-

The tag and its content are not present in this variant

Therefore it is very simple to extract any one variant from the whole document or any part of it. It is also very simple to work out, for a given piece of content, the list of ancestors in any variant. An important characteristic of this representation is that as the overlap reduces to zero so the representation reduces to the original structure.

Dominant Hierarchy

Methods for representing overlapping hierarchy often need to know the dominant hierarchy in order to know which tree structure 'overrides' the others. In this proposed representation, there is no need for a concept of a dominant hierarchy. We are at liberty to create a hierarchy that reduces the fragmentation as far as possible. Therefore it is possible to adopt various different algorithms to generate different results. The format describes how to represent overlapping hierarchy, it does not dictate what the overlap should be. Therefore another valid representation of the example above would be as follows:

<book xmlns:dx="xx" dx="A,B">

<p dx="A,B" dxTag="A">

<seg dx="A,B" dxTag="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagStart="B">Scorn not the sonnet;</l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagStart="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="B">critic, you have frowned, </l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagStart="B">Mindless of its just honours;</l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTag="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="B">with this key </l>

<l dx="A,B" dxTagStart="B">

<dx:textGroup dx="A,B">

<dx:text dx="A">SHAKESPEARE</dx:text>

<dx:text dx="B">Shakespeare</dx:text>

</dx:textGroup>

unlocked his heart;</l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTag="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="B">the melody </l>

<l dx="A,B" dxTag="B">Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch's

wound.</l>

</seg>

</p>

</book>

We can also take this a step further, and look at the representation for what might be called full fragmentation, i.e. each piece of text that has a different set of ancestors is put into a single fragment. It would also be possible to treat the paragraph element in the same way, but ideally this can be kept as a single element around all of the text, providing a clearer and simpler representation.

<book dx="A,B">

<p dx="A,B" dxTag="A">

<seg dx="A,B" dxTag="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagStart="B">Scorn not the sonnet;</l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagStart="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="B">critic, you have frowned, </l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagStart="B">Mindless of its just honours;</l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagStart="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="B">with this key </l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagStart="B">

<dx:textGroup dx="A,B">

<dx:text dx="A">SHAKESPEARE</dx:text>

<dx:text dx="B">Shakespeare</dx:text>

</dx:textGroup>

unlocked his heart;</l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagStart="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="B">the melody </l>

</seg>

<seg dx="A,B" dxTagEnd="A">

<l dx="A,B" dxTag="B">Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch's wound.</l>

</seg>

</p>

</book>

The actual hierarchy of the overlapping elements can be determined based on any criteria. One criterion might be to minimise the fragmentation. The results of an automated generation of the above by comparing the two documents and aligning them according to their text content is shown below. In this example the attribute names are shown in full, e.g. dx attribute is shown as deltaxml:deltaV2 and its content indicates whether the two documents are equal, i.e. "A=B" or not equal, i.e. "A!=B". The hierarchy is reconstructed to reduce fragmentation.

<book xmlns:deltaxml="http://www.deltaxml.com/ns/well-formed-delta-v1"

deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B"

deltaxml:version="2.1" deltaxml:content-type="full-context">

<p deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTag="A">

<seg deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTag="A">

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagStart="B"

>Scorn not the sonnet;</l>

</seg>

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagMiddle="B"> </l>

<seg deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTag="A">

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagEnd="B">critic, you have frowned,</l>

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagStart="B">Mindless of its just honours;</l>

</seg>

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagMiddle="B"> </l>

<seg deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTag="A">

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagEnd="B">with this key</l>

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagStart="B">

<deltaxml:textGroup deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B">

<deltaxml:text deltaxml:deltaV2="A"

>SHAKESPEARE</deltaxml:text>

<deltaxml:text deltaxml:deltaV2="B"

>Shakespeare</deltaxml:text>

</deltaxml:textGroup>

unlocked his heart;</l>

</seg>

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagMiddle="B"> </l>

<seg deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTag="A">

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTagEnd="B">the melody</l>

<l deltaxml:deltaV2="A!=B" deltaxml:deltaTag="B">Of this

small lute gave ease to Petrarch's wound.</l>

</seg>

</p>

</book>

In addition there are several elements that contain only white space, e.g. the second <l> element. This is because the A document contained a space between the two <seg> elements:

<seg>Scorn not the sonnet;</seg> <seg>critic, you have frowned, Mindless of its just honours;</seg>The B document had this space within the <l> element:

<l>Scorn not the sonnet; critic, you have frowned,</l>

As mentioned earlier, correct handling of white space is often very complicated because a careful distinction needs to be made between white space that can be ignored and white space that is part of the content. Element boundaries are not always word separators, for example elements that represent formatting are not considered word separators whereas a new line would be considered a word separator. This is often not clearly specified or represented in the XML schema.

The overlapping hierarchy representation described here is therefore suited to a number of different situations.

Attributes

Attributes are an important part of the XML structure, and have not yet been mentioned. Where an element appears in a particular document variant, and is not fragmented, it is simple to add the attributes onto that element as part of the start tag. When an element has been fragmented, then the attributes for that element will appear in the start tag, i.e. the element with the dxTagStart attribute. This means that any attributes that appear on a middle tag or end tag would not be relevant to a particular document variant.

This is an example of simple overlap including some attribute data:

<p>The quick brown fox. It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

<p>The quick brown fox.</p><p class="B"> It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

This is represented as:

<p dxTagStart="A" dxTag="B" dx="A,B">The quick brown fox.</p> <p dxTagEnd="A" dxTag="B" dx="A,B" class="B"> It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

This shows the class attribute but an attribute applies only to those variants where the tag is a dxTag or dxTagStart. Therefore class="B" applies only to the B document because for A this <p> is an end tag.

Changes to attributes can also be represented. This is done by converting the attribute into markup as part of a new first child of the element. Although theoretically possible to represent changes to attributes within attributes, this leads to some dedicated syntactic conventions within the attribute string, which is not easy to process. Therefore separating change attributes out into XML markup makes processing, particularly using XSLT, much easier.

This is an example of simple overlap, including some changed attribute data:

<p class="B" align="left">The quick brown fox. It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

<p class="B" align="right">The quick brown fox.</p><p> It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

This is represented as:

<p dxTagStart="A" dxTag="B" dx="A,B" class="B">

<deltaxml:attributes>

<dxa:align dx="A,B">

<deltaxml:attributeValue dx="A">left</deltaxml:attributeValue>

<deltaxml:attributeValue dx="B">right</deltaxml:attributeValue>

</dxa:align>

</deltaxml:attributes>

The quick brown fox.</p>

<p dxTagEnd="A" dxTag="B" dx="A,B"> It jumped over the lazy dog.</p>

This shows that the unchanged attribute, class="B", remains as an attribute, but the changed align attribute is represented as markup to show the two values. This is a simplified representation and full details can be found in the documentation of the DeltaXML DeltaV2.1 format [11].

The delta representation also allows an alternative representation because the <p> tag in the A document can be wrapped around the two <p> tags in the B document, as shown below:

<p dxTag="A" dx="A,B" class="B" align="left"> <p dxTag="B" dx="A,B" class="B" align="right">The quick brown fox.</p> <p dxTag="B" dx="A,B"> It jumped over the lazy dog.</p> </p>

This is, in this case, a shorter representation though it has in effect used duplication of the (unchanged) attributes and tags to show the change. However, this may be a preferred representation for some formatting elements, for example if the class attribute in a <span> is changed then it may be more useful to represent this as a different <span>. Both representations conform to the delta format.

Conclusions

This paper has described a new representation for overlapping hierarchy which is also capable of representing changes to text and attributes. This makes it suitable for some important use cases for overlapping hierarchy, particularly the representation of change between two or more variants of a document.

A significant advantage over some previous representations is that it is pure XML, and therefore can be processed using standard XML tools. The dominance of one hierarchy over another does not need to be fixed and this means that the actual hierarchy of the overlapping structures can be determined for other reasons and indeed varied throughout the document. This flexibility allows fragmentation of elements to be kept to a minimum.

The underlying data model is based on document variants and therefore is better suited to situations where the number of variants is small. Although it does scale to any number of variants, its complexity increases as the number of variants increases, e.g. each new variant has an identifier in the dx attribute so this will become longer and more difficult to interpret.

Overlapping hierarchy is a powerful tool to use in certain markup situations, though its use can lead to complex situations and any solution is also likely to look complicated. This paper is intended to contribute to the discussion as the XML community continues to strive for a simple, generic and universal solution to this problem.

References

[1] Overlap, Containment and Dominance, URN:http://www.jenitennison.com/2008/12/06/overlap-containment-and-dominance.html

[2] Modeling overlapping structures, Yves Marcoux, Michael Sperberg-McQueen, Claus Huitfeldt, http://www.balisage.net/Proceedings/vol10/html/Marcoux01/BalisageVol10-Marcoux01.html. doi:https://doi.org/10.4242/BalisageVol10.Marcoux01

[3] Markup Overlap: A Review and a Horse, Steven DeRose, http://conferences.idealliance.org/extreme/html/2004/DeRose01/EML2004DeRose01.html

[4] Multiple hierarchies: new aspects of an old solution, Andreas Witt, http://conferences.idealliance.org/extreme/html/2004/Witt01/EML2004Witt01.html

[5] Representation of overlapping structures, Michael Sperberg-McQueen, http://conferences.idealliance.org/extreme/html/2007/SperbergMcQueen01/EML2007SperbergMcQueen01.html

[6] TEI: Text Encoding Initiative, http://www.tei-c.org/index.xml

[7] OASIS Darwin Information Typing Architecture (DITA) TC, https://www.oasis-open.org/committees/tc_home.php?wg_abbrev=dita

[8] OASIS DocBook TC, https://www.oasis-open.org/committees/tc_home.php?wg_abbrev=docbook

[9] Schmidt, Desmond. “Merging Multi-Version Texts: a Generic Solution to the Overlap Problem.” Balisage Series on Markup Technologies, vol. 3 (2009), http://www.balisage.net/Proceedings/vol3/html/Schmidt01/BalisageVol3-Schmidt01.html. doi:https://doi.org/10.4242/BalisageVol3.Schmidt01

[10] Overlapping Hierarchies in DeltaV2 Format, http://www.deltaxml.com/support/documents/deltav21

[11] Two and Three Document DeltaV2 Format (patent pending), http://www.deltaxml.com/support/documents/deltav2

[1] The delta format being used here is a simplified form of the DeltaXML DeltaV2.1 format [10]. The dx attribute would normally be a deltaxml:deltaV2 and the content would indicate whether or not the documents were the same or different for this element. This distinction is not important for this paper and so has been omitted to make the examples simpler.